A City of Tradition and Modernity:

In Conversation with Madhu Nataraj

In Conversation with Madhu Nataraj

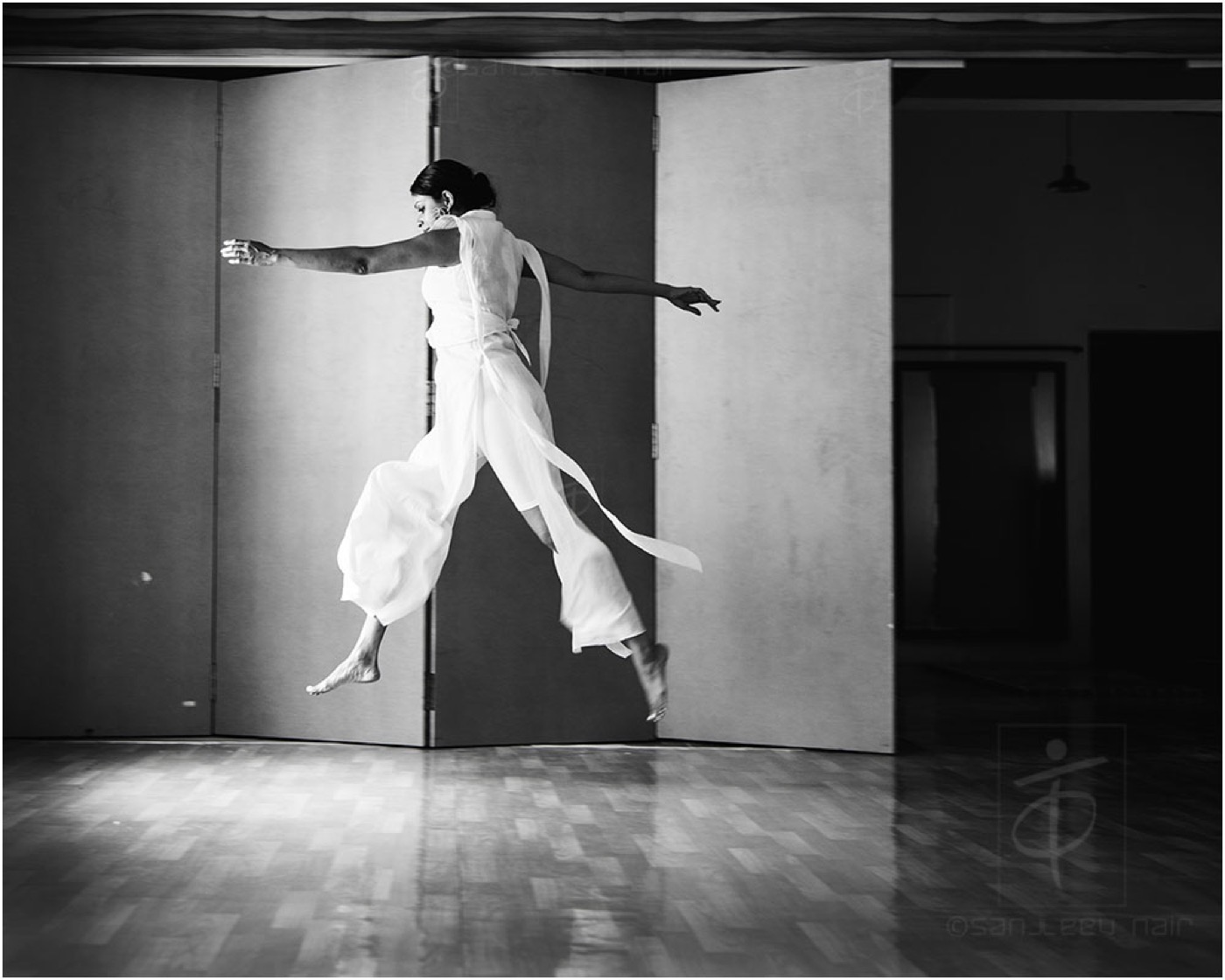

Madhu Nataraj, dancer, choreographer, and founder of Natya STEM Dance Kampni, shares, via email, her experiences of working as a contemporary dance artist in Bangalore over the last two decades.

Why did you choose to base your work in Bangalore? What is it like to be a contemporary dancer/dance maker in this city as opposed to other cities in India?

I grew up in Delhi and, after my schooling there, moved to Bangalore, where I established Karnataka’s first contemporary Indian dance company in 1995, after a stint training in the modern dance studios of New York. Bangalore personifies an amalgam and collision of cultures and thought, all seamlessly absorbed into a cosmopolitan Bangalore sensibility that excites me. The city provides me the artistic space I need to create new choreographies and projects. I find Mumbai’s buzz too distracting and Delhi’s political environment, for want of a better word, frustrating.

Bangalore coexists with tradition and modernity, and that suits my dual identity as a Contemporary and Kathak dancer.

What are the advantages and challenges of making and presenting contemporary dance work in Bangalore?

In the 1950s, my mother, Dr. Maya Rao, fought social taboos to become a dancer and to pioneer institutions that imparted systematic dance education around India. For my generation of artists who strive to sustain both companies and academies, the biggest challenge is to rise above mediocrity and constantly reinvent ourselves.

Bangalore audiences are both discerning and non-judgmental. I find them to be immensely receptive to new work. I recall when I birthed the STEM (Space. Time. Energy. Movement) Dance Kampni here 21 years ago, I was almost ostracised by some purists, but it was the audience that warmly welcomed my contemporary work. It was they, apart from a few artists, who gave my newcomer’s morale a huge impetus.

As a contemporary dancer, even today, one has to keep swimming upstream. You can imagine the scenario two decades ago! The challenges remain common to dancers from any idiom—a lack of state funding and artist management units, not enough platforms, and so on.

There are definitely more positive components that surface while presenting work in this city. Its cosmopolitan outlook, multicultural demeanour, and the gene pool of artists, entrepreneurs, and intelligentsia that forms a “no blinkers on” majority in audiences, complement the mounting and sharing of contemporary work, from the familiar to the avant-garde.

How has the city changed in terms of the resources (both training and performance opportunities) available to artists?

Bangalore hosts some of the country’s best-known performing artists and companies. Young performers find many more options and resources for studying in spaces with high standards of teaching methodologies and pedagogy.

Every locality in Bangalore, apart from the one dozen classical dance ‘shaale’, has a contemporary movement studio. Dancers are venturing into realms of therapy, healing, corporate training, civic projects, and several other exciting collaborative possibilities. The possibilities of dance as a potent medium of expression and change is being felt more now than ever before.

Has the contemporary dance audience in Bangalore evolved in any way, particularly over the last five years?

If you ask any dancer in India or overseas, they place Bangalore as one of their favourite performance venues in India. As I said before, audiences here provide a wonderful atmosphere for sharing.

Our Kampni, apart from many others, has had to take on extra portfolios over the years, becoming organiser, presenter, and curator to engage, nurture, and attract communities to watch contemporary work. We have been creating projects that take dance to its audience to reclaim its space in the public domain. Now, people are interested in following performers’ work trajectories and watching new work.

What do you envision for contemporary dance in Bangalore in the next five years and what is needed to make that happen?

I would like to see contemporary dancers emerge as important voices in the city’s artistic and socio-cultural landscape. I think dancers need to become less insular and watch more creative work by other artists from allied fields.

Live interactions are also becoming tougher thanks to Bangalore’s choking traffic scenario. Audiences prefer watching work virtually. It is time we rethink presentation possibilities and create new ecologies for dance interaction.