Archived Within Me:

In conversation with Tishani Doshi

In conversation with Tishani Doshi

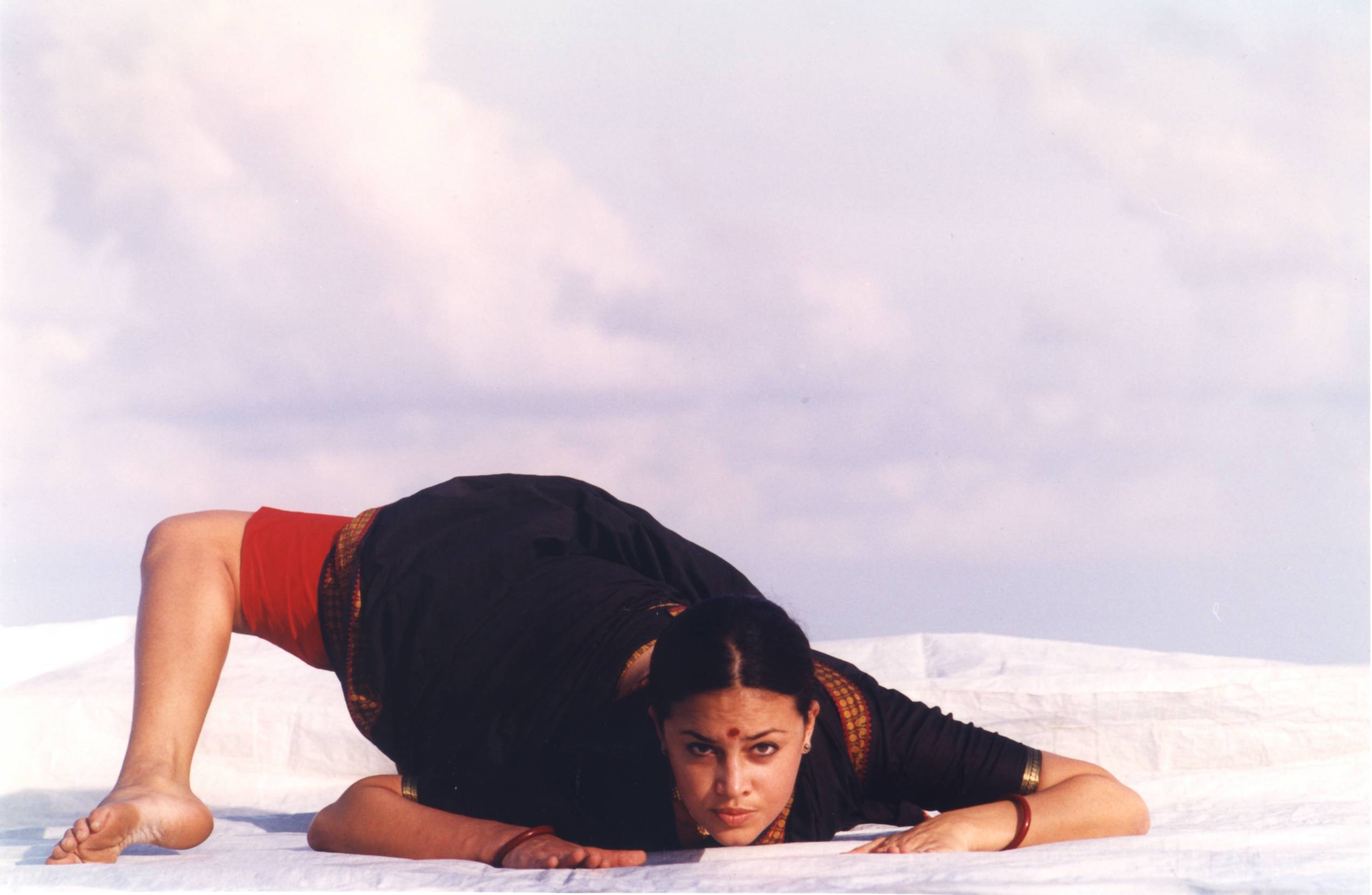

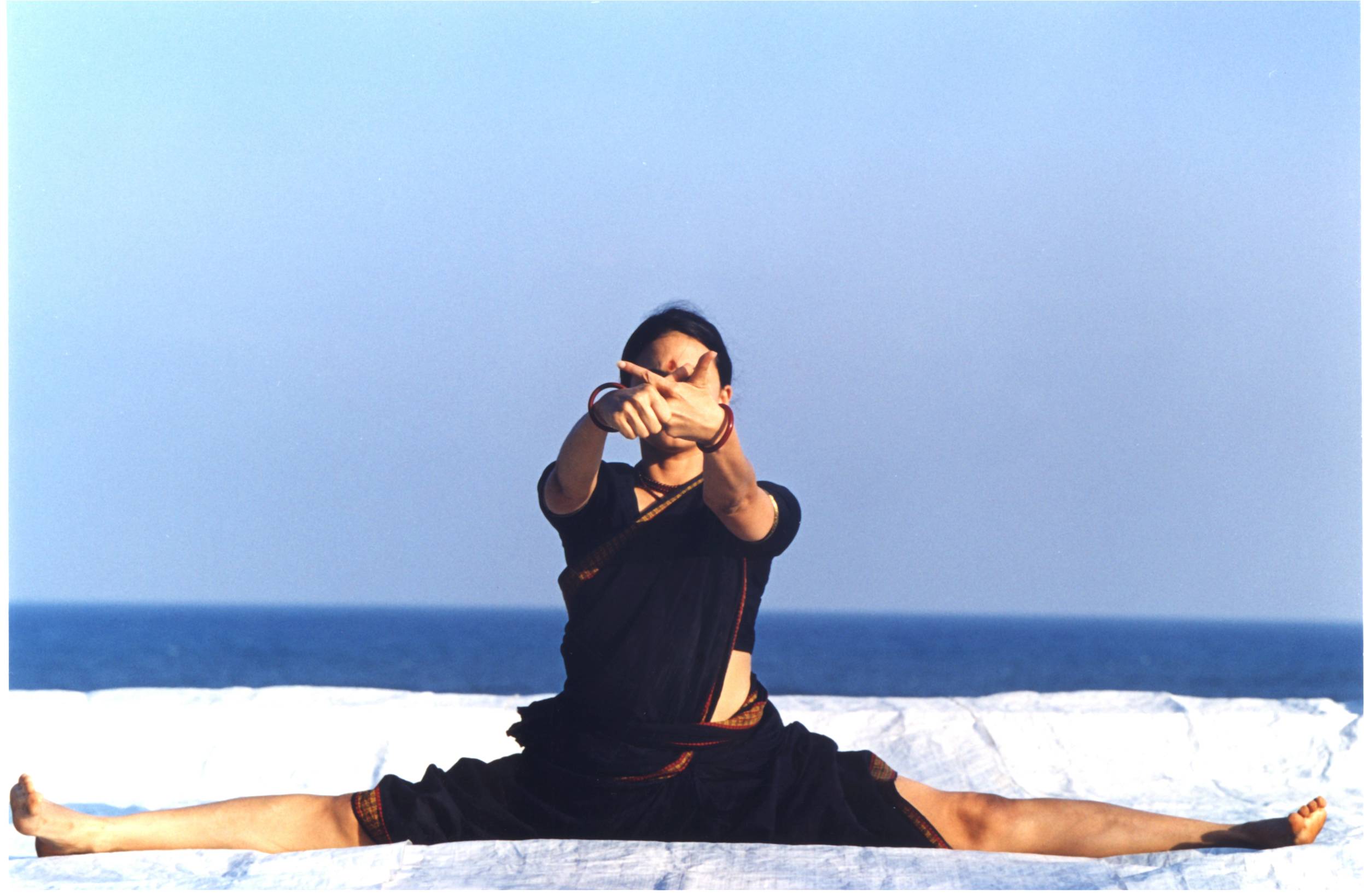

Writer and dancer Tishani Doshi speaks about her body as an archive with Sammitha Sreevathsa

Tishani Doshi has been performing Sharira, the last of Chandralekha’s choreographies, for the past 15 years. Having engaged with Sharira in Chandralekha’s presence and absence, Tishani has internalised a world of ideas, emotions, people, and relationships through the piece. Over a phone interview with Sammitha Sreevathsa, a Researcher and Documentarian of Performing Arts at Antara Collective, Tishani articulates how her body has become a site of archive for Sharira and all that it embodies.

Sammitha Sreevathsa: When I think about “body as archive” in the context of your engagement with Sharira, there is triadic relationship at play—you, Chandralekha, and the work itself. How has this relationship evolved over time?

Tishani Doshi: Let me start at the beginning of this triadic relationship. I am not a trained dancer, so when I began working with Chandralekha, I did not have any vocabulary of dance in my body, though I had been doing Yoga for many years. Chandralekha was excited to see a body which had not assumed stances that come from training in certain dance forms. She saw a body that was open and ready. So, from the beginning, Chandra’s work for me and my body was just openness.

She trained me for five years before she passed away. For the first five years, my work was with Chandra and now for the last ten years, I’ve been working without her. When Chandra was alive she was always able to make some subtle changes as she observed my body. She knew my body and I danced trusting her gaze. Now that we don’t have Chandra around we’ve had to adapt ourselves around her absence. We continue to work on the piece because in the rehearsal, and especially in the performance of Sharira, she is present.

Another change that’s taken place is obviously the change in my body. When I started I was 26, so of course my body has changed over the years and the work changes in relation to the changes in the body .

SS: In the absence of Chandra have you embodied her role in some sense?

TD: I don’t think I’ve embodied her role but I do think that I’m getting closer to embodying things that she wanted to communicate through this piece. When I started I was someone who had worked with the body but not with a true awareness of it. The first few years were such a huge leap and everything was changing inside me. Every day I was able to do a bit more than the previous day and my body was changing wildly. Chandra, and Shaji to a great degree, helped me arrive at those places of feeling able and aware. The first few years were an internal journey of understanding the possibilities of my own body, gaining confidence about the work, while the later years have been an experience of emotional and psychological connect. It is about embodying those emotions in the physical movement in order to bring a certain presence to the piece. This aspect of embodying has grown stronger over the years partly because of a certain kind of muscle memory within the body.

A huge part of it also has to do with Chandra’s absence, with performance being a way of presencing her. It is a collective and a powerful act involving not just me but Shaji, the musicians, Sadanand [Menon], the audience. Together we bring her back because this is her work, imagined by her thoroughly. So it is a powerful thing to bring her back through performance especially also because Chandra was resistant to archiving.

SS: You mentioned Chandralekha’s resistance to archiving. Can you tell me a little more about it?

TD: She was somebody who did not like for her work to be captured in stills or video. She also was a writer, which is why I found her resistance strange because I thought writers are naturally inclined towards archiving. I keep journals and write down things and for me those are precious connectors because I feel if I don’t write down these things they’ll be lost.

But then Chandra also did not like the idea of an institution and that’s probably where her resistance to archiving came from. She did not like the idea of a dance school. Her approach was different. Her approach was to put everything inside of a dancer’s body and let it continue to be shared between bodies. But I feel that if it doesn’t move from dancer to dancer then it’s lost, the work is nowhere. This was, however, the risk that Chandra was willing to take. Her attitude towards archiving her dance could also have come from the larger Indian attitude towards time and towards history, because much of our tradition has been passed without documentation. Our sense is to not pin it down but to let it flow and see how it goes and Chandra was against any kind of fossilisation of tradition.

On the other hand, I feel a certain sadness because I know that so many people slip through the cracks and disappear. The people who are remembered are not always the best of their generation or time. What Chandra did with dance in India is really revolutionary and there is no evidence of any of her work. If a hundred years from now, there is a need to talk about her work and there is no body of documentation left to be able to talk about it, then it is a loss. So we have to reconsider our approach towards archiving and whether there is way that is more fluid if we were to follow her idea on these things. For me it would be sad if it were okay that all of us who are connected with her die and then that’s it.

SS: If your body is an archive, then what is it an archive of? Do you think performance is the only way of accessing that archive?

TD: Let me tell you a little bit about what could have gotten archived within me. It is not just the choreography of Sharira because even the movements themselves are suffused with the images that Chandra collected within her by observing the world around her. So having this work (with its movements, emotions, and imagery) in my body is a way of establishing some kind of deeper lineage and connectivity through different bodies. She did not bring those images literally into her piece but people who have seen her choreographies have been able to identify in those movements the reminiscence of certain images. She was very much into icons and geometries and she knew how to take them and use them. But the images I have are not just received images. [The piece] evokes images and ideas that I explore and those come alive when I perform.

SS: “Sharira”, the word, represents body in its entirety. In your piece, there is your body, there is a representation of your body, and a performance of your body. Do you think all of your sharira, your body, make its way into the performance? Do you think there are parts of your body that get left behind?

TD: I think more than my body is there in the performance, parts of my body that I cannot access on a daily basis are present in that performance. I exceed my body and I exceed myself in the performance and I’m conscious of it. I feel it happens through a strange alchemy of other people’s energies and the actual performance. It’s so difficult to describe. It’s ethereal. But there is always a sense that it exceeds you. I suppose that’s the great temptation for wanting to continue doing it because in real life you’re always hemmed in by the limitations of the body. You are always reminded of the limitations of the body, mortality of the body, the ageing of the body and via the performance, primarily because it is so celebratory of the body, you feel like you can participate in that which is larger than yourself. But it is still coming from a place that is within the body that I cannot access just by walking on the street or doing some activity in the house. There is a very magical, very powerful mechanics of it and this exhilaration also has to do with the fact that it’s live performance.

SS: For you, as somebody who straddles the worlds of text and performance, does the quality of the text remain the same when it comes from a performer or does it take on a different quality?

TD: When I write I try to understand something I don’t know but I feel it in the body intuitively. That’s my experience of writing and it is similar to dance if you think of it as a way of performance through which you can arrive at some clarity. But because writing lacks the obvious physicality of the body that dance has, it doesn’t offer me the same sense of being more than I am. In fact, when I write I often feel less than I am. So it is somewhat inverse to dance. Of course, once you finish the text, once you have the poem, there is something magical about it. I look at old poems and wonder how I created them. Was I really a creator of a particular poem? But because the act of writing is private and is not performative, it does not have the same power for me. It has different powers but not of enabling me to almost stand outside of myself and be another being.