PariBhāsā: Scribing a Body of Words

A review on Pintu Das’ Bhasa by Chitra Chandrashekhar

AIB Attakkalari India Biennial 2021-22’s, Open Studio, showcased two original contemporary dance performances incubated at the festival, on 10th January, 7.30PM. The performance was attended by live audiences at the Rangamandala Theatre, Attakkalari Centre’s very own performance space. It was also live streamed online for remote viewers, in view of covid safety regulations. The opening performance, Bhasa – The Language, by Pintu Das, drew attention to the discomfort and damage language can cause to one’s identity and self worth. Pintu Das, a Kolkata based Dancer and Choreographer, was one of the 10 shortlisted emerging dance practitioners invited to present his latest performance at the Biennial. Pintu moulds performance and movement as a medium for social commentaries. His 2018 piece titled ‘Cha Wala’, also took a critical and dancerly view of the struggles embodied by a tea vendor’s son, torn between the choices of inheriting the family’s street side trade and migrating to jobs that are considered more “respectable”, so to say.

PC: Samuel Rajkumar, Attakkalari India Biennial 2021-22

Language is an expression in words, whether written or spoken. Rarely do we stretch this idea to include numerous other modalities sans words. While unconsciously fusing spoken words with facial expressions and hand or neck movements, we oftentimes tend to ignore the physicality of communication that lies alongside and beyond words. Not to mention, language is both overtly and covertly political. In a country where scores of languages and dialects form a part of our cultural heritage and pride, the average citizen feels inferior when they have not mastered good spoken and written English. In which case, English isn’t just a language in the Indian context. It quite effectively becomes the marker of opening and closing of opportunities and socioeconomic privileges. It certifies one’s claim to ‘class’ and ‘culture’. Language has invariably divided groups and tribes reminding people of their otherness. The fight for identity and prevention of cultural erasure is real and evident when the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution continues to amend itself for the 97th time. It deliberates on the mounting demands of the inclusion of at least 38 more languages to the 22 Scheduled languages, currently acknowledged in the 2011 census. Hindi and English are regarded as two Official languages of the Indian Republic, in an attempt to bridge the gap lingual diversity brings between people of the nation. While English is fully accepted and symbolises ‘status quo’, Hindi has often been contested by State governments, forming ripe ground for endless political disputes and debates.

In this context of language, propriety and authority, Bhasa-The Language, introduces a very remote point of view of someone who chooses a nonverbal language. Das evokes his frustrations with voices that struggle to become articulate words. The struggle is more in English than in Bangla, his native language. Worse still, is when the voice is fluent as it transmutes into bodily actions and then feared to lose its meaning and connection. His ordeals of making the audience understand his craft nonverbally without the crutches of spoken words, marks the prelude to his choreographed piece. The performance ironically opens with a question he asks in English, almost challenging the audience: “Do you understand my dance?”

As a viewer, who is new to the contemporary dance culture, one might see the performer’s body isolated in one end of the stage, stretching, falling, shaking, contorting, casting sharp and long shadows under the red and golden stage lights. Soon, one knows this is not dance like the characteristic classical dance ballets or traditional folk rhythms, celebrating well known legendary epics, mythological stories or rejoicing seasonal communal festivities. This is dance in an attempt to speak, to say something about current and contemporary ideas. It is an effort to commune around new, alternative narrative forms and content. Initially perceived to be a personal experience, it comes with possibilities of seeing common points of intersection within our complex and layered societal fabric. For me, the process of deciphering the vocabulary and grammar in Das’ movements, led to another nonverbal act of movement, called Scribing, as part of the Writing on Dance Lab that I was participating in when I watched the performance. Through live graphical capture of gestures and poses, a secondary act was unfolding. The poses rapidly drawn live and in tandem, were not accurate photographic or videographic reproductions. Instead, they transcribed the essence and visceral impressions of absorbing the performance and its energies. These gestural motion sketches were artefacts of study to reflect upon emerging meanings and associations, helping deduce and map words to actions.

PC: Samuel Rajkumar, Attakkalari India Biennial 2021-22

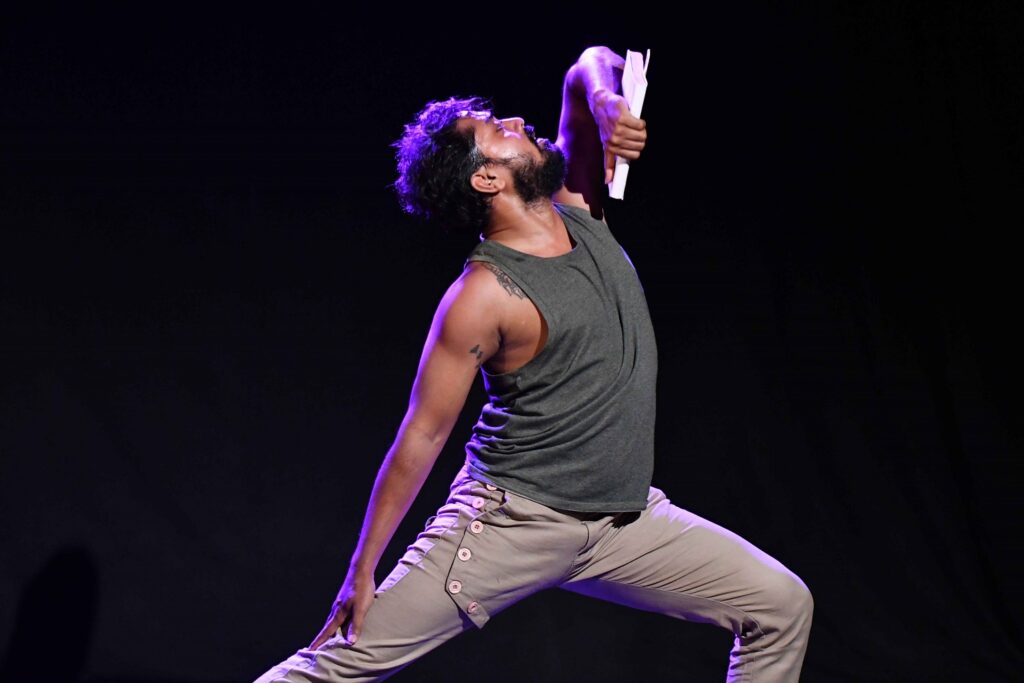

Pintu Das’ performance appeared to be non-narrative, yet the sequential progression of movements, as studied from the scribed process drawings, illuminated the hidden narrative expression. Das’ performance had a grim and dramatic feel due to the ambient lighting, to begin with. His movements started off as restricted and constrained, rising up and limply falling to the floor. He seemed to reel and writhe against the floor as if pushing his way and will through the impenetrable ground. His silent combative moves transitioned into a fight with props. First of which was an open book. Holding the open book in one hand his body was oscillating towards and away from it. Until he started to make more vigourous actions of shaking his arms, head, shoulder and neck to biting the open book and holding it in his mouth. He would bend to the floor and would shake the book as if making the words drop out of them. Eventually he rested the book shut, standing still and giving it an intent downward gaze.

He chose a red rope or string as his next prop. His body was entangled in it in no time. After much struggle with bolder, sweeping and flowing moves, he ended up on the floor, twisted and tangled in the string. Then unexpectedly, he got up and walked about the stage, pulling out the floor tapes on the stage. One is left wondering if the performance was about to end. What happened to the struggles? Why was the movement different and easier now? It also evoked discomfort, as if an act of anarchy and dissent was expressed, when he ripped off the floor tapes from the ground. The sound of the tapes was adding to the perplexity of not knowing what more was emerging. There was a nagging doubt. Was this still dance? He was ambling across the stage, following the tape lines, no more anchored to one lone corner. He held all the tape in his hands, clumping them into a messy ball and then, placed it at his feet. He looked down at it and then looked up at the audience. Then started to jog away and towards the ball of tape in one half of the stage. Finally after a few rounds he stopped and with arms and feet outstretched, forming a Y shaped pose, he ended his performance, as if making a victorious stance and a statement. In recounting the movement as it was viewed, recorded in drawings and recollected, a narrative was now being perceived. The poses, gestures and stances soon translated into words embodying strong emotions and ideas, previously unseen. The language was gradually becoming self-evident.

The tyranny he felt of expression using words and learning to do that with the help of books, tied him down, rendered him powerless and unsure of his worth and identity. His identity and innate urge to express, seems to be hidden, marred and obscured by clouds of ceaseless doubts in forever seeking confirmations, permissions, validations, conformations etc. After a fair bit of struggle with self-doubt and imposed social norms, he changes and learns to get back on his feet. Up and about, in light footsteps, he simply rolls up the messes created by the ripped off tapes. The tapes represent neat and clean conventions, now crushed and made into a manageable ball that fits in his hands. By placing the ball at his feet, he has distanced himself from the messes and confusions and can call it The Other. As if detangling himself from the tension and stresses of the expectations of mess-aging with words.

Towards the closing moments, he runs away and around the messy ball of tape but returns to face his fears. He looks down and up making sense of the otherness, rather casually. This time it feels like his ordeals are much less daunting and he is much more in control of his body, space and relationship with The Other, This time he makes a victorious declarative Y shaped Pose, almost reclaiming clarity of his renewed sense of self-assuredness. It appears that he has conquered the problem of communication, after all. He stands taller in finding his voice in his own body. He expresses comfort in his knowledge of discomfort with words while being able to share space with words. The grey casual costume he wears in a way reflects this ambiguous and matter of fact coexistence. This might be why he agreed to have an audience interaction at the end of the performance, as the convention of dance show programming goes.

Pintu Das’ performance resonated with a few in the audience who identified with his painful contortions and struggles with verbal language. It might even connect with many other Indians and non-native English speakers who share these difficulties and pressures of articulating themselves in ‘Perfect English’ words and sentences. The performance has a potential to embrace an Indian and global commentary on our inability to appreciate alternative diverse languages, beyond words. As for Pintu Das, he appears to have made peace with his ongoing strife. In an audience response, he exclaimed, “My Body language is enough.” Which makes us all think about how many other languages of expressions are we overlooking? Is there a language or Bhasa that each of us harbours with innate fluency that is neither written nor spoken nor acknowledged in words?